- Cross-compiling tools package guidelines

- Contents

- Important note

- Version compatibility

- Building a cross compiler

- Package naming

- File placement

- Example

- Hows and whys

- Why not installing into /opt ?

- What is that out-of-path executables thing?

- Troubleshooting

- What to do if compilation fails without clear message?

- What does this error [error message] means?

- Why do files get installed in wrong places?

- Introduction to cross-compiling for Linux

- Or: Host, Target, Cross-Compilers, and All That

- Host vs Target

- Why cross-compile?

- Why is cross-compiling hard?

- Portable native compiling is hard.

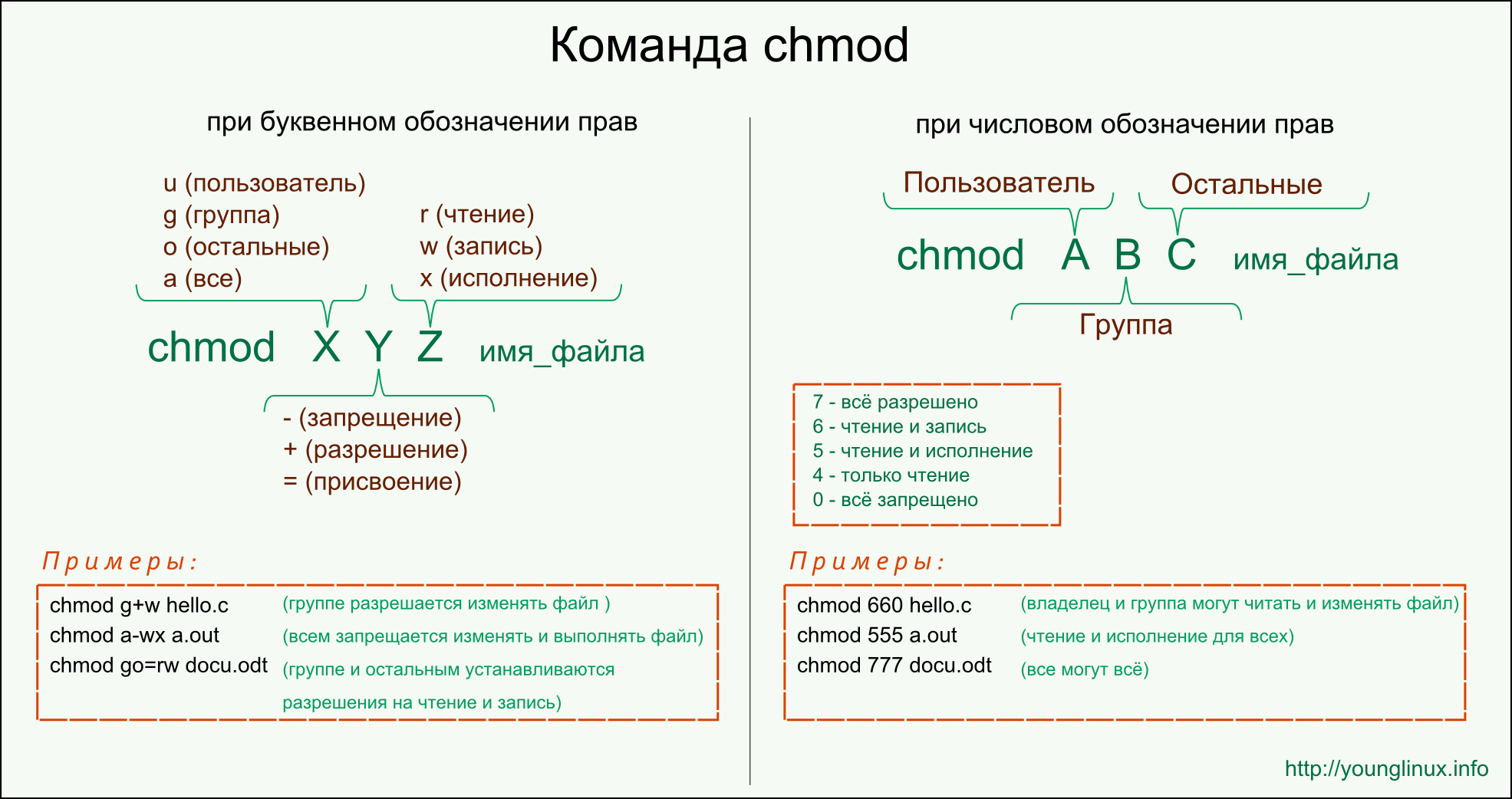

- Кросскомпиляция под ARM

- Вводная

- Инструменты

- Элементарная технология кросскомпиляции

Cross-compiling tools package guidelines

This page describes how to create packages for cross-compiler toolchains. Another method to cross-compile makes use of distcc on mixed architectures. See Distcc#Cross compiling with distcc.

Contents

Important note

This page describes the new way of doing things, inspired by the following packages:

- mingw-w64-gcc and other packages from mingw-w64-* series

- arm-none-eabi-gcc and other packages from arm-none-eabi-* series

- Other packages from arm-wince-cegcc-* series

Version compatibility

The following strategies allows you to select compatible versions of gcc, binutils, kernel and C library:

- General rules:

- there is a correlation between gcc and binutils releases, use simultaneously released versions;

- it is better to use latest kernel headers to compile libc but use —enable-kernel switch (specific to glibc, other C libraries may use different conventions) to enforce work on older kernels;

- Official repositories: you may have to apply additional fixes and hacks, but versions used by Arch Linux (or it’s architecture-specific forks) most probably can be made to work together;

- Software documentation: all GNU software have README and NEWS files, documenting things like minimal required versions of dependencies;

- Other distributions: they too do cross-compilation

- https://trac.clfs.org covers steps, necessary for building cross-compiler and mentions somewhat up-to-date versions of dependencies.

Building a cross compiler

The general approach to building a cross compiler is:

- binutils: Build a cross-binutils, which links and processes for the target architecture

- headers: Install a set of C library and kernel headers for the target architecture

- use linux-api-headers as reference and pass ARCH=target-architecture to make

- create libc headers package (process for Glibc is described here)

- gcc-stage-1: Build a basic (stage 1) gcc cross-compiler. This will be used to compile the C library. It will be unable to build almost anything else (because it cannot link against the C library it does not have).

- libc: Build the cross-compiled C library (using the stage 1 cross compiler).

- gcc-stage-2: Build a full (stage 2) C cross-compiler

The source of the headers and libc will vary across platforms.

Package naming

The package name shall not be prefixed with the word cross- (it was previously proposed, but was not adopted in official packages, probably due to additional length of names), and shall consist of the package name, prefixed by GNU triplet without vendor field or with «unknown» in vendor field; example: arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc . If shorter naming convention exists (e.g. mips-gcc ), it may be used, but this is not recommended.

File placement

Latest versions of gcc and binutils use non-conflicting paths for sysroot and libraries. Executables shall be placed into /usr/bin/ , to prevent conflicts here, prefix all of them with architecture name.

Typically, ./configure would have at least following parameters:

where your_target can be, e.g., «i686-pc-mingw32».

Example

This is PKGBUILD for binutils for MinGW. Things worth noticing are:

- specifying root directory of the cross-environment

- usage of $ <_pkgname>, $ <_target>and $ <_sysroot>variables to make the code more readable

- removal of the duplicated/conflicting files

Hows and whys

Why not installing into /opt ?

- First, according to File Hierarchy Standard, these files just belong somewhere to /usr . Period.

- Second, installing into /opt is a last measure when there is no other option.

What is that out-of-path executables thing?

This weird thing allows easier cross-compiling. Sometimes, project Makefiles do not use CC & co. variables and instead use gcc directly. If you just want to try to cross-compile such project, editing the Makefile could be a very lengthy operation. However, changing the $PATH to use «our» executables first is a very quick solution. You would then run PATH=/usr/arch/bin/:$PATH make instead of make .

Troubleshooting

What to do if compilation fails without clear message?

For error, occurred during running configure , read $srcdir/pkgname-build/config.log . For error, occurred during compilation, scroll console log up or search for word «error».

What does this error [error message] means?

Most probably you made some of non-obvious errors:

- Too many or too few configuration flags. Try to use already proven set of flags.

- Dependencies are corrupted. For example misplaced or missing binutils files may result in cryptic error during gcc configuration.

- You did not add export CFLAGS=»» to your build() function (see bug 25672 in GCC Bugzilla).

- Some —prefix / —with-sysroot combination may require directories to be writable (non-obvious from clfs guides).

- sysroot does nor yet has kernel/libc headers.

- If google-fu does not help, immediately abandon current configuration and try more stable/proven one.

Why do files get installed in wrong places?

Various methods of running generic make install line results in different results. For example, some make targets may not provide DESTDIR support and instead require install_root usage. The same for tooldir , prefix and other similar arguments. Sometimes providing parameters as arguments instead of environment variables, e.g

and vice versa may result in different outcomes (often caused by recursive self-invocation of configure/make).

Источник

Introduction to cross-compiling for Linux

Or: Host, Target, Cross-Compilers, and All That

Host vs Target

A compiler is a program that turns source code into executable code. Like all programs, a compiler runs on a specific type of computer, and the new programs it outputs also run on a specific type of computer.[1]

The computer the compiler runs on is called the host, and the computer the new programs run on is called the target. When the host and target are the same type of machine, the compiler is a native compiler. When the host and target are different, the compiler is a cross compiler.[2]

Why cross-compile?

In theory, a PC user who wanted to build programs for some device could get the appropriate target hardware (or emulator), boot a Linux distro on that, and compile natively within that environment. While this is a valid approach (and possibly even a good idea when dealing with something like a Mac Mini), it has a few prominent downsides for things like a linksys router or iPod:

Speed — Target platforms are usually much slower than hosts, by an order of magnitude or more. Most special-purpose embedded hardware is designed for low cost and low power consumption, not high performance. Modern emulators (like qemu) are actually faster than a lot of the real world hardware they emulate, by virtue of running on high-powered desktop hardware.[3]

Capability — Compiling is very resource-intensive. The target platform usually doesn’t have gigabytes of memory and hundreds of gigabytes of disk space the way a desktop does; it may not even have the resources to build «hello world», let alone large and complicated packages.

Availability — Bringing Linux up on a hardware platform it’s never run on before requires a cross-compiler. Even on long-established platforms like Arm or Mips, finding an up-to-date full-featured prebuilt native environment for a given target can be hard. If the platform in question isn’t normally used as a development workstation, there may not be a recent prebuilt distro readily available for it, and if there is it’s probably out of date. If you have to build your own distro for the target before you can build on the target, you’re back to cross-compiling anyway.

Flexibility — A fully capable Linux distribution consists of hundreds of packages, but a cross-compile environment can depend on the host’s existing distro from most things. Cross compiling focuses on building the target packages to be deployed, not spending time getting build-only prerequisites working on the target system.

Convenience — The user interface of headless boxes tends to be a bit crampled. Diagnosing build breaks is frustrating enough as it is. Installing from CD onto a machine that hasn’t got a CD-ROM drive is a pain. Rebooting back and forth between your test environment and your development environment gets old fast, and it’s nice to be able to recover from accidentally lobotomizing your test system.

Why is cross-compiling hard?

Portable native compiling is hard.

Most programs are developed on x86 hardware, where they are compiled natively. This means cross-compiling runs into two types of problems: problems with the programs themselves and problems with the build system.

The first type of problem affects all non-x86 targets, both for native and for cross-builds. Most programs make assumptions about the type of machine they run on, which must match the platform in question or the program won’t work. Common assumptions include:

Word size — Copying a pointer into an int may lose data on a 64 bit platform, and determining the size of a malloc by multiplying by 4 instead of sizeof(long) isn’t good either. Subtle security flaws due to integer overflows are also possible, ala «if (x+y

Footnote 1: The most prominent difference between types of computers is what processor is executing the programs, but other differences include library ABIs (such as glibc vs uClibc), machines with configurable endianness (arm vs armeb), or different modes of machines that can run both 32 bit and 64 bit code (such as x86 on x86-64).

Footnote 2: When building compilers, there’s a third type called a «canadian cross», which is a cross compiler that doesn’t run on your host system. A canadian cross builds a compiler that runs on one target platform and produces code for another target machine. Such a foreign compiler can be built by first creating a temporary cross compiler from the host to the first target, and then using that to build another cross-compiler for the second target. The first cross-compiler’s target becomes the host the new compiler runs on, and the second target is the platform the new compiler generates output for. This technique is often used to cross-compile a new native compiler for a target platform.

Footnote 3: Modern desktop systems are sufficiently fast that emulating a target and natively compiling under the emulator is actually a viable strategy. It’s significantly slower than cross compiling, requires finding or generating a native build environment for the target (often meaning you have to set up a cross-compiler anyway), and can be tripped up by differences between the emulator and the real hardware to deploy on. But it’s an option.

Footnote 4: This is why cross-compile toolchains tend to prefix the names of their utilities, ala «armv5l-linux-gcc». If that was simply called «gcc» then the host and native compiler couldn’t be in the $PATH at the same time.

Источник

Кросскомпиляция под ARM

Достаточно давно хотел освоить сабж, но всё были другие более приоритетные дела. И вот настала очередь кросскомпиляции.

В данном посте будут описаны:

- Инструменты

- Элементарная технология кросскомпиляции

- И, собственно, HOW2

Кому это интересно, прошу под кат.

Вводная

Одно из развивающихся направлений в современном IT это IoT. Развивается это направление достаточно быстро, всё время выходят всякие крутые штуки (типа кроссовок со встроенным трекером или кроссовки, которые могут указывать направление, куда идти (специально для слепых людей)). Основная масса этих устройств представляют собой что-то типа «блютуз лампочки», но оставшаяся часть являет собой сложные процессорные системы, которые собирают данные и управляют этим огромным разнообразием всяких умных штучек. Эти сложные системы, как правило, представляют собой одноплатные компьютеры, такие как Raspberry Pi, Odroid, Orange Pi и т.п. На них запускается Linux и пишется прикладной софт. В основном, используют скриптовые языки и Java. Но бывают приложения, когда необходима высокая производительность, и здесь, естественно, требуются C и C++. К примеру, может потребоваться добавить что-то специфичное в ядро или, как можно быстрее, высчитать БПФ. Вот тут-то и нужна кросскомпиляция.

Если проект не очень большой, то его можно собирать и отлаживать прямо на целевой платформе. А если проект достаточно велик, то компиляция на целевой платформе будет затруднительна из-за временных издержек. К примеру, попробуйте собрать Boost на Raspberry Pi. Думаю, ожидание сборки будет продолжительным, а если ещё и ошибки какие всплывут, то это может занять ох как много времени.

Поэтому лучше собирать на хосте. В моём случае, это i5 с 4ГБ ОЗУ, Fedora 24.

Инструменты

Для кросскомпиляции под ARM требуются toolchain и эмулятор платформы либо реальная целевая платформа.

Т.к. меня интересует компиляция для ARM, то использоваться будет и соответствующий toolchain.

Toolchain’ы делятся на несколько типов или триплетов. Триплет обычно состоит из трёх частей: целевой процессор, vendor и OS, vendor зачастую опускается.

- *-none-eabi — это toolchain для компиляции проекта работающего в bare metal.

- *eabi — это toolchain для компиляции проекта работающего в какой-либо ОС. В моём случае, это Linux.

- *eabihf — это почти то же самое, что и eabi, с разницей в реализации ABI вызова функций с плавающей точкой. hf — расшифровывается как hard float.

Описанное выше справедливо для gcc и сделанных на его базе toolchain’ах.

Сперва я пытался использовать toolchain’ы, которые лежат в репах Fedora 24. Но был неприятно удивлён этим:

Поискав, наткнулся на toolchain от компании Linaro. И он меня вполне устроил.

Второй инструмент- это QEMU. Я буду использовать его, т.к. мой Odroid-C1+ пал смертью храбрых (нагнулся контроллер SD карты). Но я таки успел с ним чуток поработать, что не может не радовать.

Элементарная технология кросскомпиляции

Собственно, ничего необычного в этом нет. Просто используется toolchain в роли компилятора. А стандартные библиотеки поставляются вместе с toolchain’ом.

Выглядит это так:

Какие ключи у toolchain’а можно посмотреть на сайте gnu, в соответствующем разделе.

Для начала нужно запустить эмуляцию с интересующей платформой. Я решил съэмулировать Cortex-A9.

После нескольких неудачных попыток наткнулся на этот how2, который оказался вполне вменяемым, на мой взгляд.

Ну сперва, само собою, нужно заиметь QEMU. Установил я его из стандартных репов Fedor’ы.

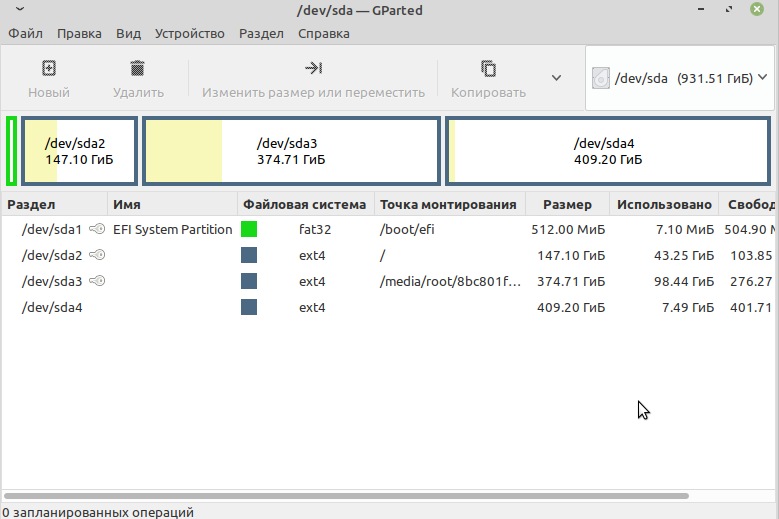

Далее создаём образ жёсткого диска, на который будет установлен Debian.

По этой ссылке скачал vmlinuz и initrd и запустил их в эмуляции.

Далее просто устанавливаем Debian на наш образ жёсткого диска (у меня ушло

После установки нужно вынуть из образа жёсткого диска vmlinuz и initrd. Делал я это по описанию отсюда.

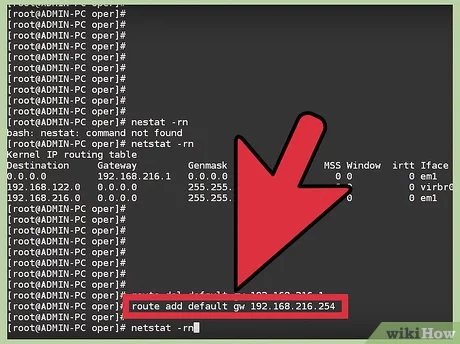

Сперва узнаём смещение, где расположен раздел с нужными нам файлами:

Теперь по этому смещению примонтируем нужный нам раздел.

Копируем файлы vmlinuz и initrd и размонтируем жёсткий диск.

Теперь можно запустить эмуляцию.

И вот заветное приглашение:

Теперь с хоста по SSH можно подцепиться к симуляции.

Теперь можно и собрать программку. По Makefile’у ясно, что будет калькулятор. Простенький.

Собираем на хосте исполняемый файл.

Отмечу, что проще собрать с ключом -static, если нет особого желания предаваться плотским утехам с библиотеками на целевой платформе.

Копируем исполняемый файл на таргет и проверяем.

Собственно, вот такая она, эта кросскомпиляция.

UPD: Подправил информацию по toolchain’ам по комментарию grossws.

Источник