- Landoflinux

- Linux Boot Sequence Explained

- BIOS — Basic Input Output System

- MBR — Master Boot Record

- GRUB — The Grand Unified Bootloader

- Kernel

- Directories /etc/rc0.d through /etc/rc6.d

- How to determine your current runlevel

- Switching between runlevels — init and telinit

- shutdown

- Frequently Used Options with shutdown

- An introduction to the Linux boot and startup processes

- Ever wondered what it takes to get your system ready to run applications? Here’s what is going on under the hood.

- Subscribe now

- The boot process

- BIOS POST

- GRUB2

- Stage 1

- Stage 1.5

- Stage 2

- Kernel

- The startup process

- systemd

- Issues

- Conclusions

Landoflinux

Linux Boot Sequence Explained

The Linux boot process is the name given to the startup procedures/order that your system goes through to load its operating system. In the following example, I will be referring to booting Linux on x86 architecture.

Note: This boot sequence is based around systems that use sysV init. Most newer systems will be using a system called systemd. Systemd will be covered later within our tutorials.

BIOS — Basic Input Output System

When an x86 computer is booted your system will look for a program called «BIOS«, Basic Input output System. The BIOS code is a piece of read only code. The BIOS is responsible for initiating the first steps of the boot process. When the BIOS code is executed, it will look for any peripherals present, it will then look for a drive to use for the booting of the system. Normally you can press ‘F12’ or ‘F2’ to enter your BIOS and change the boot sequence order. Once a valid boot loader has been found and loaded into memory, full control is then passed. In simple terms, the BIOS loads and executes the MBR (Master Boot Record).

MBR — Master Boot Record

The Master Boot Record is generally found on the first sector of the bootable disk (less than 512 bytes in size). This will probably be «/dev/sda» or «/dev/hda» on older systems. The master boot record can be broken down into three sections. The Primary Bootloader which takes up the first 446 bytes of information. Next is the Partition Table which takes the next 64 bytes of information. The last 2 bytes are taken by the MBR validation check. The MBR contains information about your boot loader. On older systems this was «Lilo» and on newer systems this is «GRUB» (Grand Unified Bootloader). Basically the MBR loads and executes the boot loader.

GRUB — The Grand Unified Bootloader

GRUB is one of the most commonly used bootloader on Linux systems. There are currently two versions in use. GRUB 1.0 which is still in use on older supported systems and GRUB 2.0 which normally ships with most new systems. Using GRUB gives you the ability to load the kernel image of choice if you have more than one on your system, otherwise the default option will be loaded. Various other modifications can be made at this point in the boot process. These will be covered in more detail later. GRUB configuration files are normally located within the following locations:

GRUB 1.0 — OpenSUSE/Debian — «/boot/grub/menu.lst»

GRUB 2.0 — Debian — «/boot/grub/grub.conf» or «/boot/grub/grub.cfg»

Other systems such as Fedora often provide a symbolic link from «/etc/grub.conf» which points to «/boot/grub/grub.conf»

Example of GRUB config file under CentOS 6.3 running under VirtualBox:

Kernel

The Kernel is responsible for mounting the root filesystem. Initiates the «init process» /sbin/inittab program. This is the first process to run on your system and will always have the process Id of «1» (PID of 1). initrd is an «Initial RAM Disk«, this space is used by the kernel as a temporary root filesystem. Various drivers are stored here which allow access to your system and partitions.

This is the /etc/inittab which decides on which runlevel to load at boot. There are various runlevels available and each has a specific roll or function if selected. The following are the available runlevels (depending on your system):

| Run Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Halt the system. Runlevel 0 is used by System Administrators to shutdown the system quickly. |

| 1, s, S | Single User Mode, often called Maintenance Mode. In this mode, system services such as network interfaces, web servers, and file sharing are not started. This mode is usually used for interactive filesystem maintenance. The three choices 1, s, and S are all the same. |

| 2 | Multiuser Mode. On Debian based systems, this is the default runlevel. On Red Hat based systems this is multiuser mode without NFS file sharing or the X Window System (the graphical user interface). |

| 3 | On Red Hat based systems, this is the default multiuser mode, which runs everything except the X Window System. Runlevels 3, 4 and 5 are not usually used on Debian based systems. |

| 4 | Not Used. |

| 5 | On Red Hat based systems this is the Full multi user mode with login screen. Similar to runlevel 3 with the exception that the X11 Graphical user Interface is started. |

| 6 | Reboot the system. |

Directories /etc/rc0.d through /etc/rc6.d

The scripts in /etc/init.d are not directly executed by the init process. Instead, each of the directories /etc/rc0.d through /etc/rc6.d contain symbolic links to scripts in the /etc/init.d directory. So when the system is started and a runlevel is selected, the scripts within the relevant directory are executed in strict order. For example, when the init process enters runlevel N, it examines all of the links in the associated rcN.d directory. These links have a special naming convention:

SNNname and KNNname. Here the «S» stands for «start» and the «K» stands for «kill«. Each particular runlevel defines a state in which services are running and all others are not running. The «S» prefix is used to mark files for all services that should be running (started). The «K» prefix is used for all other services, which should not be running. The «NN» is a numerical order that is used to depict the sequence in which the scripts should run. The lowest number is executed first and the highest last.

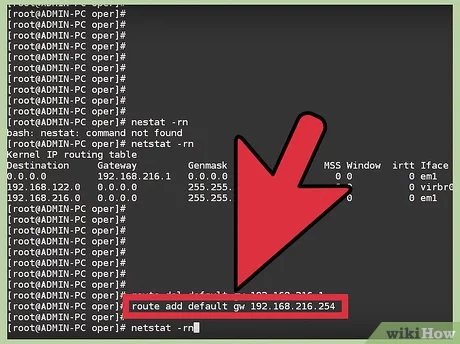

How to determine your current runlevel

If you need to check what your current runlevel is, you can check this quickly by issuing the command «runlevel» or by issuing the command «who -r«.

The above example indicates that I am currently in runlevel «5» and the letter «N» indicates that there has been no change to the current runlevel since boot.

Switching between runlevels — init and telinit

To switch between runlevels is quite easy providing you are the root user and that you have permission to change to a different runlevel. The «init» or «telinit» command sends a request to the init process to change to a specified runlevel. Generally you would use the init command to shutdown your system, switch to Single User Mode or simply reboot the system. The syntax of the command is as follows:

init n

In the above the «n» refers to the runlevel. For example, to switch to runlevel 3 on a Red Hat based system, we could issue: init 3. To shut our system down we could issue:init 0. To reboot the system, we could issue: init 6. telinit is an alternative command to use instead of init. The syntax for using telinit remains the same as init.

shutdown

If you are going to initiate a shutdown of your system and there are other users logged in to your system, it is always polite to notify them first. To do this, we would use the shutdown command. The shutdown command will accept times and a broadcast message:

shutdown [options] time [warning_message]

Frequently Used Options with shutdown

-f : Fast boot, skips fsck file checking on reboot.

-h : Halts system after shutdown.

-k : Send pretend Shutdown Warning Message.

-r : Reboot after shutdown.

-F : Force Filesystem checks on the next boot.

shutdown and reboot immediately

Reboot in 5 minutes with message

shutdown and halt system at 22:00hrs

shutdown and halt immediately

Источник

An introduction to the Linux boot and startup processes

Ever wondered what it takes to get your system ready to run applications? Here’s what is going on under the hood.

Subscribe now

Get the highlights in your inbox every week.

Understanding the Linux boot and startup processes is important to being able to both configure Linux and to resolving startup issues. This article presents an overview of the bootup sequence using the GRUB2 bootloader and the startup sequence as performed by the systemd initialization system.

In reality, there are two sequences of events that are required to boot a Linux computer and make it usable: boot and startup. The boot sequence starts when the computer is turned on, and is completed when the kernel is initialized and systemd is launched. The startup process then takes over and finishes the task of getting the Linux computer into an operational state.

Overall, the Linux boot and startup process is fairly simple to understand. It is comprised of the following steps which will be described in more detail in the following sections.

- BIOS POST

- Boot loader (GRUB2)

- Kernel initialization

- Start systemd, the parent of all processes.

Note that this article covers GRUB2 and systemd because they are the current boot loader and initialization software for most major distributions. Other software options have been used historically and are still found in some distributions.

The boot process

The boot process can be initiated in one of a couple ways. First, if power is turned off, turning on the power will begin the boot process. If the computer is already running a local user, including root or an unprivileged user, the user can programmatically initiate the boot sequence by using the GUI or command line to initiate a reboot. A reboot will first do a shutdown and then restart the computer.

BIOS POST

The first step of the Linux boot process really has nothing whatever to do with Linux. This is the hardware portion of the boot process and is the same for any operating system. When power is first applied to the computer it runs the POST (Power On Self Test) which is part of the BIOS (Basic I/O System).

When IBM designed the first PC back in 1981, BIOS was designed to initialize the hardware components. POST is the part of BIOS whose task is to ensure that the computer hardware functioned correctly. If POST fails, the computer may not be usable and so the boot process does not continue.

BIOS POST checks the basic operability of the hardware and then it issues a BIOS interrupt, INT 13H, which locates the boot sectors on any attached bootable devices. The first boot sector it finds that contains a valid boot record is loaded into RAM and control is then transferred to the code that was loaded from the boot sector.

The boot sector is really the first stage of the boot loader. There are three boot loaders used by most Linux distributions, GRUB, GRUB2, and LILO. GRUB2 is the newest and is used much more frequently these days than the other older options.

GRUB2

GRUB2 stands for «GRand Unified Bootloader, version 2» and it is now the primary bootloader for most current Linux distributions. GRUB2 is the program which makes the computer just smart enough to find the operating system kernel and load it into memory. Because it is easier to write and say GRUB than GRUB2, I may use the term GRUB in this document but I will be referring to GRUB2 unless specified otherwise.

GRUB has been designed to be compatible with the multiboot specification which allows GRUB to boot many versions of Linux and other free operating systems; it can also chain load the boot record of proprietary operating systems.

GRUB can also allow the user to choose to boot from among several different kernels for any given Linux distribution. This affords the ability to boot to a previous kernel version if an updated one fails somehow or is incompatible with an important piece of software. GRUB can be configured using the /boot/grub/grub.conf file.

GRUB1 is now considered to be legacy and has been replaced in most modern distributions with GRUB2, which is a rewrite of GRUB1. Red Hat based distros upgraded to GRUB2 around Fedora 15 and CentOS/RHEL 7. GRUB2 provides the same boot functionality as GRUB1 but GRUB2 is also a mainframe-like command-based pre-OS environment and allows more flexibility during the pre-boot phase. GRUB2 is configured with /boot/grub2/grub.cfg.

The primary function of either GRUB is to get the Linux kernel loaded into memory and running. Both versions of GRUB work essentially the same way and have the same three stages, but I will use GRUB2 for this discussion of how GRUB does its job. The configuration of GRUB or GRUB2 and the use of GRUB2 commands is outside the scope of this article.

Although GRUB2 does not officially use the stage notation for the three stages of GRUB2, it is convenient to refer to them in that way, so I will in this article.

Stage 1

As mentioned in the BIOS POST section, at the end of POST, BIOS searches the attached disks for a boot record, usually located in the Master Boot Record (MBR), it loads the first one it finds into memory and then starts execution of the boot record. The bootstrap code, i.e., GRUB2 stage 1, is very small because it must fit into the first 512-byte sector on the hard drive along with the partition table. The total amount of space allocated for the actual bootstrap code in a classic generic MBR is 446 bytes. The 446 Byte file for stage 1 is named boot.img and does not contain the partition table which is added to the boot record separately.

Because the boot record must be so small, it is also not very smart and does not understand filesystem structures. Therefore the sole purpose of stage 1 is to locate and load stage 1.5. In order to accomplish this, stage 1.5 of GRUB must be located in the space between the boot record itself and the first partition on the drive. After loading GRUB stage 1.5 into RAM, stage 1 turns control over to stage 1.5.

Stage 1.5

As mentioned above, stage 1.5 of GRUB must be located in the space between the boot record itself and the first partition on the disk drive. This space was left unused historically for technical reasons. The first partition on the hard drive begins at sector 63 and with the MBR in sector 0, that leaves 62 512-byte sectors—31,744 bytes—in which to store the core.img file which is stage 1.5 of GRUB. The core.img file is 25,389 Bytes so there is plenty of space available between the MBR and the first disk partition in which to store it.

Because of the larger amount of code that can be accommodated for stage 1.5, it can have enough code to contain a few common filesystem drivers, such as the standard EXT and other Linux filesystems, FAT, and NTFS. The GRUB2 core.img is much more complex and capable than the older GRUB1 stage 1.5. This means that stage 2 of GRUB2 can be located on a standard EXT filesystem but it cannot be located on a logical volume. So the standard location for the stage 2 files is in the /boot filesystem, specifically /boot/grub2.

Note that the /boot directory must be located on a filesystem that is supported by GRUB. Not all filesystems are. The function of stage 1.5 is to begin execution with the filesystem drivers necessary to locate the stage 2 files in the /boot filesystem and load the needed drivers.

Stage 2

All of the files for GRUB stage 2 are located in the /boot/grub2 directory and several subdirectories. GRUB2 does not have an image file like stages 1 and 2. Instead, it consists mostly of runtime kernel modules that are loaded as needed from the /boot/grub2/i386-pc directory.

The function of GRUB2 stage 2 is to locate and load a Linux kernel into RAM and turn control of the computer over to the kernel. The kernel and its associated files are located in the /boot directory. The kernel files are identifiable as they are all named starting with vmlinuz. You can list the contents of the /boot directory to see the currently installed kernels on your system.

GRUB2, like GRUB1, supports booting from one of a selection of Linux kernels. The Red Hat package manager, DNF, supports keeping multiple versions of the kernel so that if a problem occurs with the newest one, an older version of the kernel can be booted. By default, GRUB provides a pre-boot menu of the installed kernels, including a rescue option and, if configured, a recovery option.

Stage 2 of GRUB2 loads the selected kernel into memory and turns control of the computer over to the kernel.

Kernel

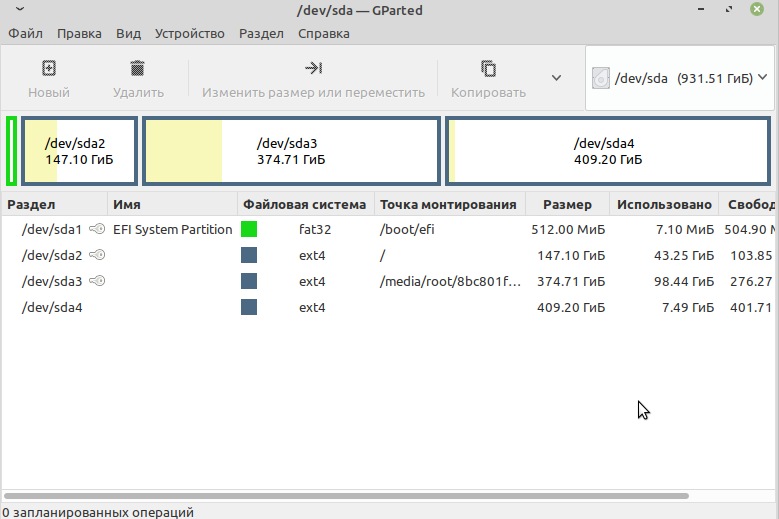

All of the kernels are in a self-extracting, compressed format to save space. The kernels are located in the /boot directory, along with an initial RAM disk image, and device maps of the hard drives.

After the selected kernel is loaded into memory and begins executing, it must first extract itself from the compressed version of the file before it can perform any useful work. Once the kernel has extracted itself, it loads systemd, which is the replacement for the old SysV init program, and turns control over to it.

This is the end of the boot process. At this point, the Linux kernel and systemd are running but unable to perform any productive tasks for the end user because nothing else is running.

The startup process

The startup process follows the boot process and brings the Linux computer up to an operational state in which it is usable for productive work.

systemd

systemd is the mother of all processes and it is responsible for bringing the Linux host up to a state in which productive work can be done. Some of its functions, which are far more extensive than the old init program, are to manage many aspects of a running Linux host, including mounting filesystems, and starting and managing system services required to have a productive Linux host. Any of systemd’s tasks that are not related to the startup sequence are outside the scope of this article.

First, systemd mounts the filesystems as defined by /etc/fstab, including any swap files or partitions. At this point, it can access the configuration files located in /etc, including its own. It uses its configuration file, /etc/systemd/system/default.target, to determine which state or target, into which it should boot the host. The default.target file is only a symbolic link to the true target file. For a desktop workstation, this is typically going to be the graphical.target, which is equivalent to runlevel 5 in the old SystemV init. For a server, the default is more likely to be the multi-user.target which is like runlevel 3 in SystemV. The emergency.target is similar to single user mode.

Note that targets and services are systemd units.

Table 1, below, is a comparison of the systemd targets with the old SystemV startup runlevels. The systemd target aliases are provided by systemd for backward compatibility. The target aliases allow scripts—and many sysadmins like myself—to use SystemV commands like init 3 to change runlevels. Of course, the SystemV commands are forwarded to systemd for interpretation and execution.

| SystemV Runlevel | systemd target | systemd target aliases | Description |

| halt.target | Halts the system without powering it down. | ||

| 0 | poweroff.target | runlevel0.target | Halts the system and turns the power off. |

| S | emergency.target | Single user mode. No services are running; filesystems are not mounted. This is the most basic level of operation with only an emergency shell running on the main console for the user to interact with the system. | |

| 1 | rescue.target | runlevel1.target | A base system including mounting the filesystems with only the most basic services running and a rescue shell on the main console. |

| 2 | runlevel2.target | Multiuser, without NFS but all other non-GUI services running. | |

| 3 | multi-user.target | runlevel3.target | All services running but command line interface (CLI) only. |

| 4 | runlevel4.target | Unused. | |

| 5 | graphical.target | runlevel5.target | multi-user with a GUI. |

| 6 | reboot.target | runlevel6.target | Reboot |

| default.target | This target is always aliased with a symbolic link to either multi-user.target or graphical.target. systemd always uses the default.target to start the system. The default.target should never be aliased to halt.target, poweroff.target, or reboot.target. |

Table 1: Comparison of SystemV runlevels with systemd targets and some target aliases.

Each target has a set of dependencies described in its configuration file. systemd starts the required dependencies. These dependencies are the services required to run the Linux host at a specific level of functionality. When all of the dependencies listed in the target configuration files are loaded and running, the system is running at that target level.

systemd also looks at the legacy SystemV init directories to see if any startup files exist there. If so, systemd used those as configuration files to start the services described by the files. The deprecated network service is a good example of one of those that still use SystemV startup files in Fedora.

Figure 1, below, is copied directly from the bootup man page. It shows the general sequence of events during systemd startup and the basic ordering requirements to ensure a successful startup.

The sysinit.target and basic.target targets can be considered as checkpoints in the startup process. Although systemd has as one of its design goals to start system services in parallel, there are still certain services and functional targets that must be started before other services and targets can be started. These checkpoints cannot be passed until all of the services and targets required by that checkpoint are fulfilled.

So the sysinit.target is reached when all of the units on which it depends are completed. All of those units, mounting filesystems, setting up swap files, starting udev, setting the random generator seed, initiating low-level services, and setting up cryptographic services if one or more filesystems are encrypted, must be completed, but within the sysinit.target those tasks can be performed in parallel.

The sysinit.target starts up all of the low-level services and units required for the system to be marginally functional and that are required to enable moving on to the basic.target.

Figure 1: The systemd startup map.

After the sysinit.target is fulfilled, systemd next starts the basic.target, starting all of the units required to fulfill it. The basic target provides some additional functionality by starting units that re required for the next target. These include setting up things like paths to various executable directories, communication sockets, and timers.

Finally, the user-level targets, multi-user.target or graphical.target can be initialized. Notice that the multi-user.target must be reached before the graphical target dependencies can be met.

The underlined targets in Figure 1, are the usual startup targets. When one of these targets is reached, then startup has completed. If the multi-user.target is the default, then you should see a text mode login on the console. If graphical.target is the default, then you should see a graphical login; the specific GUI login screen you see will depend on the default display manager you use.

Issues

I recently had a need to change the default boot kernel on a Linux computer that used GRUB2. I found that some of the commands did not seem to work properly for me, or that I was not using them correctly. I am not yet certain which was the case, and need to do some more research.

The grub2-set-default command did not properly set the default kernel index for me in the /etc/default/grub file so that the desired alternate kernel did not boot. So I manually changed /etc/default/grub GRUB_DEFAULT=saved to GRUB_DEFAULT=2 where 2 is the index of the installed kernel I wanted to boot. Then I ran the command grub2-mkconfig > /boot/grub2/grub.cfg to create the new grub configuration file. This circumvention worked as expected and booted to the alternate kernel.

Conclusions

GRUB2 and the systemd init system are the key components in the boot and startup phases of most modern Linux distributions. Despite the fact that there has been controversy surrounding systemd especially, these two components work together smoothly to first load the kernel and then to start up all of the system services required to produce a functional Linux system.

Источник