- Linux Guide/How Linux Works

- Contents

- The Linux Philosophy [ edit | edit source ]

- Core components of a Linux system [ edit | edit source ]

- Boot loader [ edit | edit source ]

- Kernel [ edit | edit source ]

- Daemons [ edit | edit source ]

- Shell [ edit | edit source ]

- X Window Server [ edit | edit source ]

- Window Manager [ edit | edit source ]

- Desktop Environment [ edit | edit source ]

- File System [ edit | edit source ]

- Devices as files [ edit | edit source ]

- Where are the drive letters? [ edit | edit source ]

- Users [ edit | edit source ]

- File permissions [ edit | edit source ]

- Осваиваем Linux за три недели

- Зачем сейчас нужно уметь обращаться с Linux?

- Как Linux связан с освоением других дисциплин?

- Почему для этого нужен отдельный курс?

- Что в Linux интересного?

- Как проверять решение задач на курсе по Linux? Это вообще возможно?

- А почему всё-таки Linux так хорош?

Linux Guide/How Linux Works

Contents

The Linux Philosophy [ edit | edit source ]

Linux is built with a certain set of unifying principles in mind. Understanding these principles is very helpful in understanding how the system works as a whole. They are known as the «Linux Way», which is derived from the philosophy behind the UNIX system.

The Linux Way can be summarized as:

- Use programs that do only one task, but do it well.

- To accomplish complex tasks, use several programs linked together.

- Store information in human-readable plain text files whenever it is possible.

- There is no «one true way» to do anything.

- Prefer commandline tools over graphical tools.

Most traits of Linux are a consequence of these principles. In accordance with them, a Linux system is built out of small, replaceable components. We will examine the most important of them in more detail. Those are: the boot loader, the kernel, the shell, the X window server, the window manager and the desktop environment. After that, we will have a look at the file system in Linux. Finally, we will discuss the security of a computer running Linux.

Core components of a Linux system [ edit | edit source ]

Boot loader [ edit | edit source ]

This is the part of the system that is executed first. When you have only one operating system installed, it simply loads the kernel (see below). If you happen to have multiple operating systems or multiple versions of the Linux kernel installed, it allows you to choose which one you want to start. The most popular bootloaders are GRUB (GRand Unified Bootloader) and Lilo (LInux LOader). Most users don’t need to care about the boot loader, because it is installed and configured automatically. Actually, the boot Loader creates the boot sequence that the Linux Kernel requires, loading the kernel and some device drivers required for early boot process into memory (as part of so-called «initramfs»), and starting the kernel.

Kernel [ edit | edit source ]

The kernel is the central component of the system that communicates directly with the hardware. In fact, the name «Linux» properly refers to a particular kind of this piece of software. It allows programs to ignore the differences between various computers. The kernel allocates system resources like memory, processor time, hard disk space and external devices to the programs running on the computer. It separates each program from the others, so that when one of them encounters an error, others are not affected. Most users don’t need to worry about the kernel in day-to-day use, but certain software or hardware will require or perform better with certain kernel versions.

Daemons [ edit | edit source ]

In a typical Linux system there are various services running as processes in the background, taking care of things like configuring your network connection, responding to connected USB devices, managing user logins, managing filesystems, etc. They are often called «daemons», because they are running silently and are mostly invisible to the user.

One of these «daemons», started by the kernel after it finishes booting itself, is called init , and its role is to start the rest of the system, including all other «daemons» and graphical sessions.

Different Linux distributions use different init systems. The traditional init system used since the old Unix era, is Sys V init (referring to the System V Unix). But recently many distributions have switched to more modern init systems, such as systemd .

Shell [ edit | edit source ]

The shell, sometimes also called «command line», implements a textual interface that allows you to run programs and control the system by entering commands from the keyboard. Without a shell (or something that can replace it, like a desktop environment) making your system actually do something would be difficult. The shell is just a program; there are several different shells for Linux, each of which offering somewhat different features. Most Linux systems use the Bourne Again Shell (Bash). Linux shells support multitasking (running several programs at once).

X Window Server [ edit | edit source ]

The X window server is a graphical replacement for the command shell. It is responsible for drawing graphics and processing input from the keyboard, mouse, tablets and other devices. The X server is network transparent; that is, it allows you to work in a graphical environment both on your own computer and on a remote computer to which you connect across a network. The X server that is most used today is X.Org. Most graphical programs need only the X server to run, so they can be used under any window manager and desktop environment.

Window Manager [ edit | edit source ]

The window manager is a program that communicates with the X server. Its task is managing windows. It is responsible for drawing the window borders, bringing a window to the front when you click it, moving it on the screen and hiding it when you minimize its program. Examples of popular window managers are:

- Metacity — GNOME Desktop Environment window manager

- KWin — KDE window manager

- Xfwm — Xfce window manager, a lightweight manager designed to consume as little resources as possible without compromising usability

- Compiz Fusion — an advanced window manager with lots of eye candy like customizable window animations, multiple desktops placed on a cube that you can rotate with your mouse, transparent window borders, wobbling windows while dragging them, etc.

Desktop Environment [ edit | edit source ]

Desktop environments such as GNOME Desktop Environment, KDE and Xfce are collections of programs designed to present a consistent user interface for most common tasks. They are what most people mean when they say «operating system» even though they are only a piece of the whole operating system. Multiple desktop environments can coexist on the same machine. They can be easily installed and after installation the user will be given a way to select which DE to start the session with.

File System [ edit | edit source ]

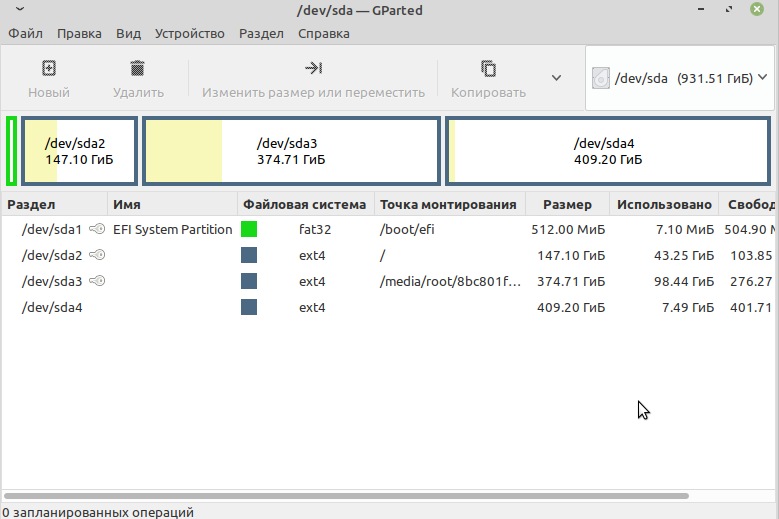

There are several file systems that Linux-based distributions use. They are BTRFS, EXT3/4, VFS, NILFS, and SquashFS.

The hard drive of your computer has a rather simple interface. It only accepts commands like «read block no. 550923 and put it in memory address 0x0021A400». Suppose you are editing a piece of text and want to save it on the disk. Using block numbers (addresses) to identify pieces of data, like your text, is awkward: not only would you have to tell your program where to save the file using raw block numbers, you would have to make sure that these blocks aren’t already being used for family photos, your music collection, or even your system’s kernel. To solve this, files were introduced. A file is an area of the disk which stores data and which has a name (like «example.txt»). Files are organized in collections called directories. Directories can contain other directories, in a tree-like structure. Each file can be uniquely identified by a «path,» which describes its place in the directory hierarchy. For the remainder of this section, it will be assumed that you are familiar with files, directories, and paths.

In Linux, the top-level directory is called the root directory. Every file and directory in the system must be a descendant of the root directory. (It is common to talk about directories using the terminology of family relations, like «parent,» «child,» «descendant,» «ancestor,» «sibling,» and so forth.) Names of files and directories can contain all characters except the null character (which is impossible to enter from the keyboard) and the «/» character. An example path would be:

This path refers to a file called «error.log» which is found in a directory called «apache,» which is a subdirectory of a directory called «logs,» which is subdirectory of a directory called «var,» which is a subdirectory of the root directory. The root directory doesn’t have a name like the other; it is just denoted with a «/» character at the beginning of the path.

The root directory usually contains only a small number of subdirectories. The most important are:

- bin — programs needed to perform basic tasks, i.e. change a directory or copy a file

- dev — special files that represent hardware devices

- etc — configuration files

- home — contains private directories of users

- media or mnt — Mount point for external drives connected to this computer, i.e. CDs or USB keys

- tmp — temporary files

- usr — programs installed on the computer

- var — variable data produced by programs, like error logs

Devices as files [ edit | edit source ]

Just as files can be written to and read, devices in the computer system may send and receive data. Because of this, Linux represents the devices connected to the system as files in the /dev directory. These files can not be renamed or moved (they are not stored on any disk). This approach greatly simplifies application programming. If you want to send something to another computer through a serial port, you don’t even need another program — you simply write to the file /dev/ttyS0, which represents a serial port. In the same manner the file representing the sound card (/dev/dsp) can be read to capture the sound from an attached microphone, or written to in order to produce sound through the speakers.

Where are the drive letters? [ edit | edit source ]

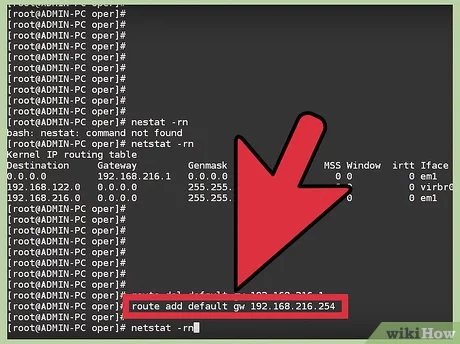

If you have used Windows, you might be surprised that there are no drive letters in Linux. The root directory represents the drive on which the system is installed (C: in Windows). Other drives can be «mounted» or «unmounted» in any directory (preferably, an empty one) in the file system. By mounting a disk, you attach the root directory of this disk to a directory in the file system. After that, you can access the disk like it were a part of your system disk. For example: if you have a disk that contains a directory text, which in turn contains a file called linux-intro.tex and you mount this drive in the directory /media/usbkey, you can access the file linux-intro.tex through the path /media/usbkey/text/linux-intro.tex.

In most Linux distributions, USB keys and CDs are automatically mounted when they are inserted or attached, and the default mount directory is a subdirectory of /media or /mnt. For example, your first CD-ROM drive might be mounted at /media/cdrom0, while the contents of a USB key might be accessible through /media/usb0. You may manually change the mount directory, but you will have to learn two shell commands and know the device file that represents your drive to do that (the one we talked about in the preceding section — disks also get their file representation in the /dev directory). We will cover this subject later.

Users [ edit | edit source ]

The user is a metaphor for somebody or something interacting with the system. Users are identified by a user name and a password. Internally, each user has a unique number assigned, which is called a user ID, or UID for short. You only need to know your UID in some rare situations. Users can additionally be organized in groups. There is one special user in all Linux systems, which has the user name «root» and UID 0. It is also called the superuser. The superuser can do anything and is not controlled in any way by the security mechanisms. Having such a user account is very useful for administrative tasks and configuring the system. In some distributions (like Ubuntu) direct access to the root account is disabled and other mechanisms are used instead.

If you have more than one user account on a Linux system, you do not need to log out and back again to switch impersonations. There are special shell commands that allow you to access files and execute programs as other users, provided you know their user names and passwords. Thanks to this mechanism, you can spend most of the time as a user with low-privileges and switch to a higher-privileged account only if you need to.

The advantage of running as a non-privileged user is that any mistakes you happen to make are very unlikely to damage the system. System-critical components can only be altered by the root user.

File permissions [ edit | edit source ]

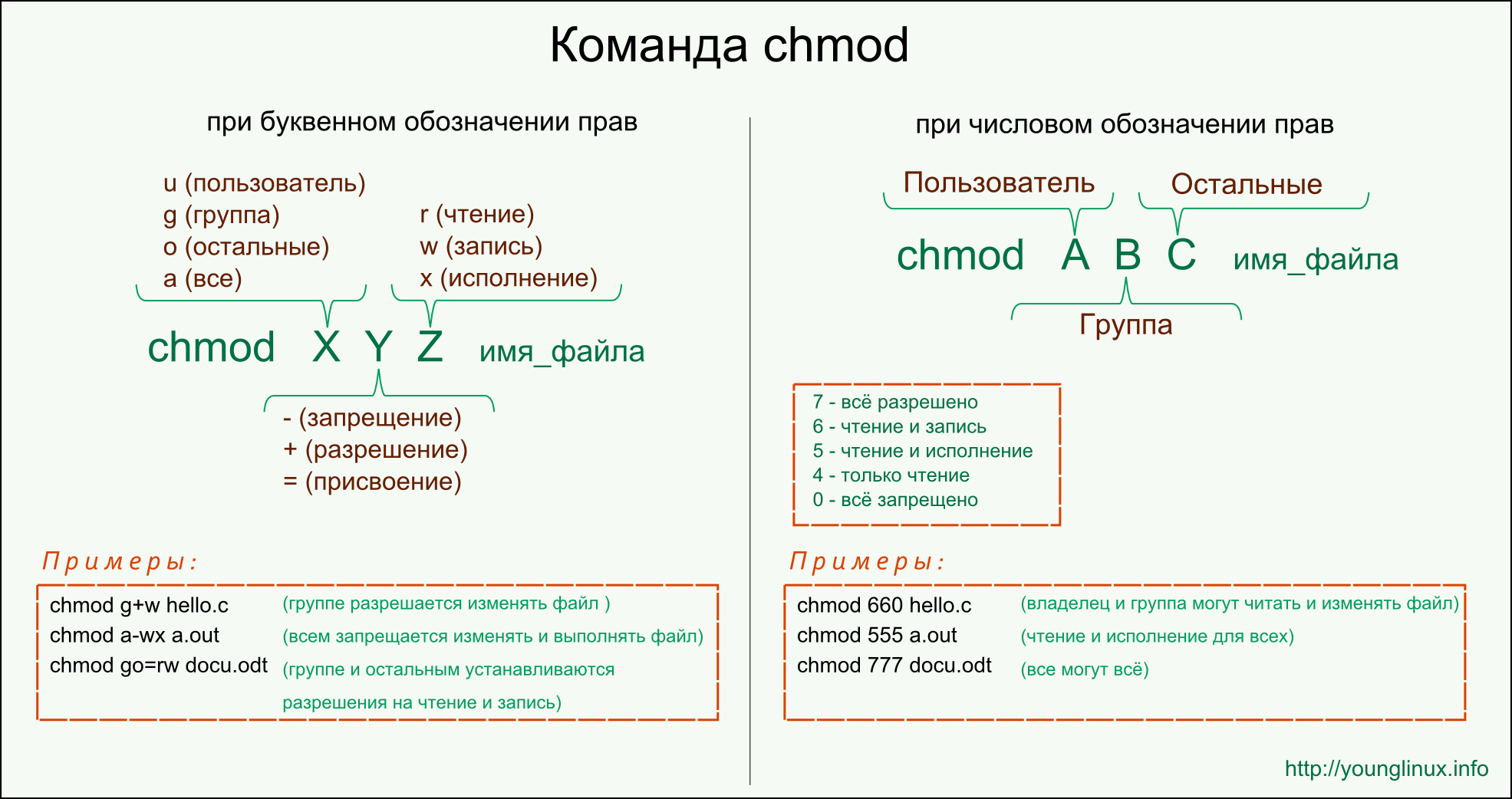

Users exist to control the extent to which people and programs using the system can control it. This is accomplished by a system of file permissions. Each file belongs to one of the users — that is, each file has an owner. Additionally, a file can be assigned to a group of users, but the owner must be a member of that group. Each file has three kinds of permissions: read, write and execute. These permissions can be assigned to three kinds of owner relations: owner, group and other. Other includes all users who are not the owner of the file and do not belong to the group which owns the file. Only the file owner or the superuser (root) can change the permissions or ownership of a file.

This system allows precise control over who can do what on a given computer. Users can be prevented from modifying system files by removing the «write» permission from them, or from executing certain commands by removing the «execute» permission. Notice that users may be allowed to execute programs but not alter them. This is very important, since most Linux systems include a compiler that allows you to create your own programs.

File permissions are usually given as three octal digits (each from 0 to 7). The digits represent the permissions for, respectively, owner, group and other users. Each digit is the sum of permission codes: 1 for execute, 2 for write and 4 for read. For example, «755» allows everyone to read or execute the file, but only its owner can write it. «400» allows the owner to read the file, and no one else is allowed to do anything. «540» allows the owner to read or execute the file, group members to only read the file and other users to do nothing.

chmod (change mode), chown (change owner), and chgrp (change group) are used to change file permissions.

Источник

Осваиваем Linux за три недели

Идея вводного курса по работе с Linux возникла у нас с коллегами довольно давно. Я с 2011 года занимаюсь биоинформатикой в Лаборатории алгоритмической биологии СПбАУ РАН (тут и тут мой напарник писал про то, чем мы занимаемся). Сразу нужно сказать, что работа биоинформатика без Linux практически невозможна, поскольку большинство биоинформатических программ созданы именно под эту операционную систему и работают только на ней.

В силу того, что это область на стыке наук, мы постоянно общаемся с биологами. Биологам же сейчас приходится работать с очень большими объемами данных, поэтому умение использовать Linux, оптимальную для подобных задач операционную систему, становится необходимым навыком. На самом деле, речь не только об умении обращаться с Linux, а в целом о компьютерной грамотности: какие существуют правила работы на сервере, как загружать и эффективно хранить файлы с данными, какие программы запускать для их обработки и как это сделать и т.д. — все те вещи, которые как упрощают и ускоряют вашу работу, так и значительно облегчают совместную деятельность с коллегам. Несмотря на то, что разобраться с Linux можно и самостоятельно, почитав умные книжки и сайты, для людей из не технической среды это часто вызывает определенные сложности и многие сдаются на начальных этапах освоения этой ОС (например, на знакомстве с командной строкой).

На основе нашего опыта я и мой коллега Андрей Пржибельский (@andrewprzh) изначально собирались провести несколько занятий для биологов по компьютерной грамотности. А потом эта идея выросла в трехнедельный открытый онлайн-курс (MOOC) Института биоинформатики на русском языке, который позже был сужен до именно введения в Linux, как отправной точки, — поскольку вместить все в три недели оказалось очень и очень трудно. Курс уже начался и оказался достаточно популярен (на данный момент на него записалось более пяти тысяч человек), но первый дедлайн по заданиям — 24 ноября, поэтому еще можно присоединиться без потери баллов или просто изучать курс в свободном режиме (все материалы останутся открытыми).

Про саму подготовку первого в нашей жизни онлайн-курса, если сообществу интересно, мы напишем отдельный пост — это совсем не так просто и быстро, как может показаться на первый взгляд.

Но сначала хотелось бы остановиться на ответах на вопросы, которые нам задавали чаще всего. При подготовке курса мы общались с самыми разными людьми и столкнулись с тем, что многие совсем не понимают, где используется Linux, и не догадывались, что система может быть им полезна. Итак:

Зачем сейчас нужно уметь обращаться с Linux?

Многие не замечают, но Linux уже вокруг нас. Все Android устройства работают на Linux, большинства серверов в Интернете также используют эту операционную систему и есть множество других примеров. Конечно, можно продолжать пользоваться всеми этими вещами и не зная Linux, но освоив основы этой системы, можно лучше понять поведение окружающих вас вещей. Кроме того, при работе с большим объемом данных, Linux просто необходим, ведь большинство сложных вычислений над огромными массивами данных выполняются именно на компьютерах под управлением Linux. И это не случайный выбор: большинство вычислительных задач выполняются на Linux гораздо быстрее, чем на Windows или Mac OS X.

Как Linux связан с освоением других дисциплин?

Огромная доля научного ПО, особенно программ для обработки больших данных (например, в области биоинформатики) разработана специально под Linux. Это значит, что эти приложения просто не могут быть запущены под Windows или Mac OS X. Так что если вы не умеете работать в Linux, то автоматически лишаетесь возможности использовать самые современные научные наработки. Кроме того, изучая Linux, вы лучше понимаете как работает компьютер, ведь вы сможете отдавать ему команды практически напрямую.

Почему для этого нужен отдельный курс?

У Linux очень много возможностей, которые полезно знать и, конечно же, уметь ими воспользоваться в нужный момент. К счастью, современные версии Linux гораздо более дружелюбны к пользователям, чем их собратья еще 5-6 лет назад. Сейчас можно не мучиться часами и даже днями ночами после установки системы, чтобы настроить себе выход в Интернет, печать на принтере, раскладки клавиатуры и так далее. Любой желающий сможет начать использовать Linux так же, как он использовал Windows или Mac OS X уже после минимального знакомства с этой системой, которое будет исчисляться минутами. Однако возможности Linux гораздо шире «повседневного» использования. Рассказать обо всей функциональности Linux просто невозможно даже за трехнедельный курс. Однако мы стараемся научить слушателей использовать большинство базовых возможностей Linux, а самое главное, надеемся, что прошедшие курс смогут успешно продолжить освоение Linux самостоятельно.

Что в Linux интересного?

Для нас Linux похож на очень интересную книгу, которую вы прочитали и с удовольствием рекомендуете своим друзьям и даже чувствуете зависть от того, что у них знакомство с этим произведением еще впереди. Единственная разница в том, что хоть мы и знакомы с Linux уже почти по 10 лет, не можем сказать, что «прочитали» его целиком. В нем постоянно можно найти что-то новое для себя, узнать что многие вещи, которые ты привык делать одним способом, можно сделать совершенно по-другому — гораздо проще и быстрее.

Чем больше знакомишься с Linux, тем он становится интереснее. И от первоначального желания «поскорее бы выключить и перезагрузиться в родную и знакомую Windows (Mac OS X)» вы вскоре переходите в состояние «хм, а тут не так и плохо» и еще немного позже в «как я вообще мог работать в этой Windows?!». А еще изучая Linux вы порою можете почувствовать себя немного хакером или героем фильма про программистов =)

Наш курс состоит из краткого обзора основных возможностей Linux, однако для начинающих пользователей этого должно быть вполне достаточно, чтобы заинтересоваться Linux и немного погрузиться в его философию. Например, большую часть курса мы будем проводить за работой в терминале, так что у новичков должно возникнуть и привыкание и понимание преимуществ такого подхода к управлению компьютером. Для более продвинутых пользователей могут представлять интерес отдельные занятия курса — например, про работу с удаленным сервером или программирование на языке bash. Полная программа онлайн-курса доступна здесь.

Как проверять решение задач на курсе по Linux? Это вообще возможно?

Ответ на этот вопрос был нетривиальным — мы долго думали, как проверять задания (например, что пользователь установил Linux себе на компьютер или отредактировал файл в определенном редакторе) и как придумать интересные задачи, чтобы действительно показать реальную работу с Linux. Для каких-то тем получились довольно любопытные подходы. Например, специально для курса был добавлен новый тип задач на платформе Stepic — подключение к удалённому серверу (и открытие «терминала») прямо в окне браузера — по отзывам первых пользователей, им понравилось. Конечно, в первый раз не обошлось без шероховатостей, но, в целом, всё работает довольно хорошо. Про техническую сторону этого вопроса скоро появится отдельный пост от разработчиков. Пример такого задания (для просмотра вживую можно записаться на курс):

Нужно сказать, что не все пользователи воспринимали задачи с юмором. Например, мы проверяли навык установки программ на Linux на примере программы VLC. Нужно было установить ее в свою систему одним из рассказанных способов, потом открыть справку о программе, найти фамилию первого автора и ввести ее в форму для проверки. Каких только комментариев мы не наслушались про это задание 🙂 А ошибались люди в основном в том, что вводили имя и фамилию, или только имя, или часть фамилии (а она там двойная, через дефис!). В общем, если решитесь проходить курс, то читайте условия задач внимательнее и это сэкономит много времени и нервов! Правда с тем же автором было замечание и по делу, оказалось что в старых версиях VLC он идет аж на 14 месте, так что добавили в проверку еще одного автора, который первый среди «старого» списка (и, кстати, третий в «новом»).

А почему всё-таки Linux так хорош?

Вопрос, конечно, неоднозначный. На мой взгляд одним из ключевых преимуществ Linux перед Windows или Mac OS X является то, что эта операционная система разрабатывается огромным сообществом программистов по всему миру, а не в двух, пусть и очень больших компаниях (Microsoft и Apple). Исходный код этой системы открыт, и каждый может познакомится с внутренним устройством Linux или поучаствовать в его развитии. Разработчики развивают его не только для пользователей-покупателей, но и для самих себя, с чем и связан такой большой прогресс в развитии и многие другие его преимущества. В качестве «бонусов» для обычных пользователей: Linux бесплатный, на Linux практически нет вирусов (а сами разработчики вирусов зачастую сидят под Linux!), существую огромное число версий этой системы и каждый может выбрать понравившуюся именно ему!

И напоследок хотелось бы рассказать о своем первом знакомстве с Linux именно в рабочем процессе (до этого был еще отдельный курс по учебе, но из него я не очень много вынес, к сожалению). Этот случай меня так впечатлил, что помню его до сих пор. Когда я работал на кафедре в Политехе на 3-ем курсе мне понадобилось запускать одну программу для обработки данных. Программа была написана на С++, а работали мы тогда в Windows XP. Запусков нужно было сделать много, были они довольно однотипные и занимали обычно пару минут. За это время ничего другого сделать на компьютере было нельзя — он полностью «подвисал», так что можно было поболтать с другими сотрудниками или просто прогуляться по кабинету. Примерно через пару недель таких запусков, мой научный руководитель посоветовал попробовать мне сделать всё тоже самое, но не в Windows, а в Linux. Я тогда подумал «ну какая разница», но так руководителя уважал, то программу перекомпилировал и его совет исполнил. Какового же было моё удивление, когда я запустил ту же самую программу на тех же самых данных и получил результат (естественно, точно такой же) за несколько секунд! Я даже со стула встать не успел, не то что прогуляться…

Кстати, помимо нашего русскоязычного онлайн-курса по Linux, существует хороший англоязычный вводный курс от Linux Foundation, про который уже писали на хабре. Судя по сайту, он снова начнется 5 января 2015.

Если вы знаете ещё интересные онлайн-курсы или обучающие материалы по азам Linux, будем рады увидеть ссылки на них в комментариях.

Источник