- Why You Should Use Linux to Learn Programming

- It’s Free

- It’s Been Around Forever

- It’s Easy to Build Programs

- Learn the ways of Linux-fu, for free.

- Grasshopper

- Getting Started

- Command Line

- Text-Fu

- Advanced Text-Fu

- User Management

- Permissions

- Processes

- Packages

- Journeyman

- Devices

- The Filesystem

- Boot the System

- Kernel

- Process Utilization

- Logging

- Networking Nomad

- Network Sharing

- Network Basics

- Subnetting

- Routing

- Network Config

- Troubleshooting

- Recommended Resources

- How to Create a First C Program on Linux

Why You Should Use Linux to Learn Programming

Linux is popular with programmers, and for good reason. Linux and Unix has long been a mainstay of computer science education for a long time. If you’ve always wanted to learn programming, whether you want to develop software professionally or just for fun, there’s no better platform to cut your teeth on.

If you’re still not convinced, here are a few reasons why you should use Linux (or any other Unix, including the BSDs) to learn how to program.

It’s Free

Linux is best known for the fact that all the distributions and most of the software is available free of charge. While Microsoft and Apple development tools can cost upwards of hundreds of dollars, Linux, since its user base is comprised of a lot of developers, has lots of programming tools available for free. Some distros have them pre-installed, some make them available through their package repositories. Browsing the available tools will make you feel, as Homer Simpson put it, like a kid in some kind of store. There are editors, compilers and interpreters for nearly every language ever created, debuggers, parser generators, you name it. If these programs actually cost money, you’d probably be able to buy a small house for the money you paid for them.

In addition, as Richard Stallman famously put it, these programs are also “free as in speech, not as in beer.” Stallman is best known for founding the free software movement back in the ’80s, which was an attempt to make sure that users could always get access to software that had the source code available. Whether you call it “free software” or “open source,” reading the source code to programs is the best way to learn programming. Imagine if you wanted to become a great writer but weren’t allowed to read any books. How could you be expected to produce anything worthwhile without knowing about the history of literature.

It’s Been Around Forever

While Microsoft changes its tools frequently, it’s an apparent attempt to simply charge their customers for their products by forcing them to upgrade.

Linux, on the other hand, builds on the Unix tradition by offering tried-and-true tools. You can pick up a book on Unix from the ’80s and much of it will still be applicable to a modern Linux distribution today. Although the GNU project and others have rewritten and enhanced many of the classic Unix tools, they still work pretty much the same as they did back in the ’70s and ’80s.

It’s Easy to Build Programs

One reason Unix and Linux has been popular with programmers all these years is that it’s incredibly easy to build complex programs without a whole lot of effort.

The most notable feature of Unix is the way shells handle input and output. It’s easy to send the output from one program to the other. A trivial example would be to send the output of the “who” command that shows everyone logged into a system into the less pager:

If you tried to code up something similar in C from scratch, you’d be looking at at least a thousand lines of code. The use of pipes, on the other hand, turns Unix and Linux into software LEGO, which lets you build complex programs out of a simple set of building blocks. This is also the reason serious Linux users prefer the command line. It’s almost impossible to pipe input from graphical programs.

If you’re thinking of getting started, why not pick a Linux distribution and start exploring today?

David Delony is a writer for Make Tech Easier

Источник

Learn the ways of Linux-fu, for free.

Get updates about new courses and lessons!

Grasshopper

Getting Started

What is Linux? Get started with choosing a distribution and installation.

Command Line

Learn the fundamentals of the command line, navigating files, directories and more.

Text-Fu

Learn basic text manipulation and navigation.

Advanced Text-Fu

Navigate text like a Linux spider monkey with vim and emacs.

User Management

Learn about user roles and management.

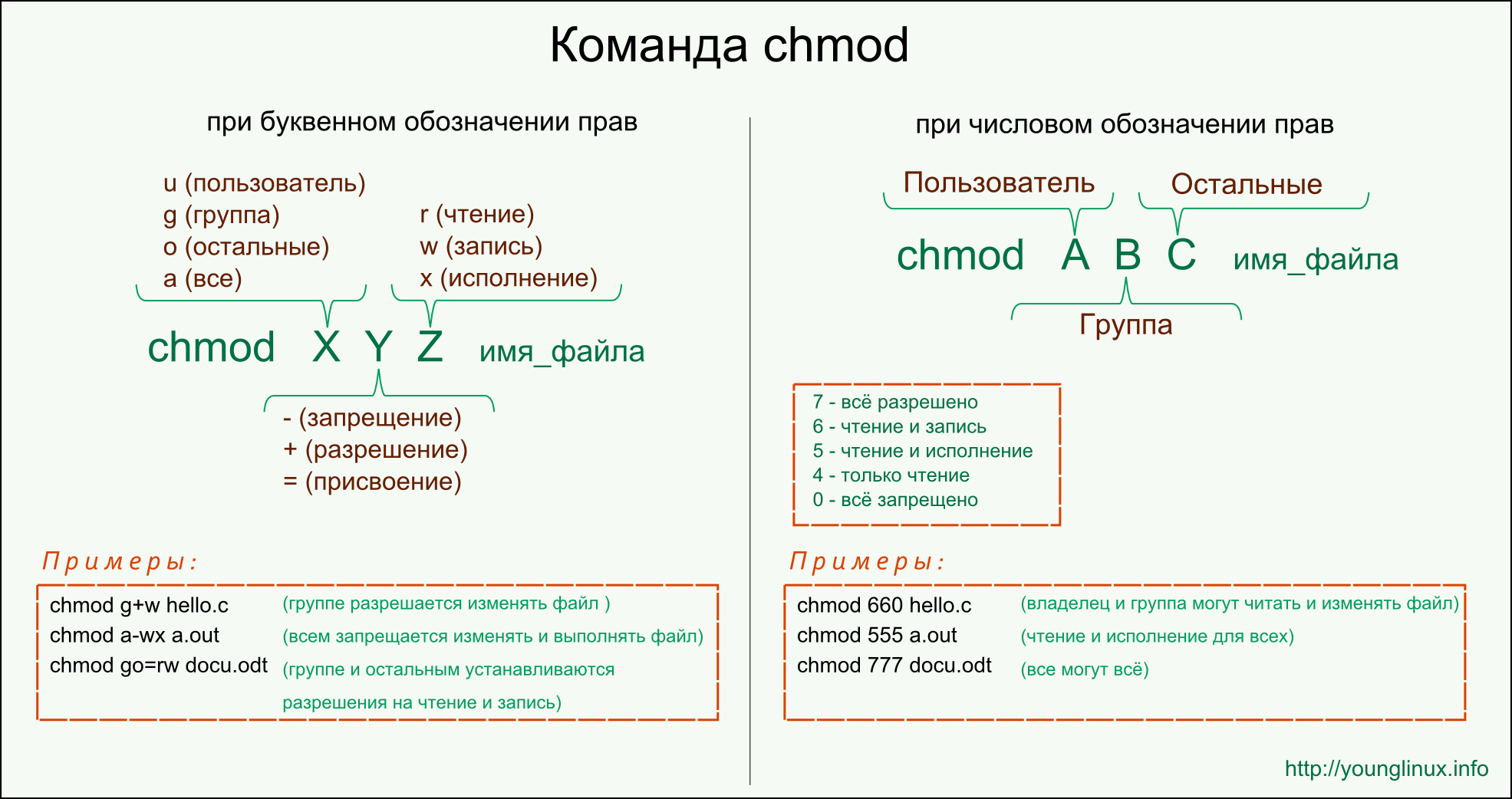

Permissions

Learn about permission levels and modifying permissions.

Processes

Learn about the running processes on the system.

Packages

Learn all about the dpkg, apt-get, rpm and yum package management tools.

Journeyman

Devices

Learn about Linux devices and how they interact with the kernel and user space.

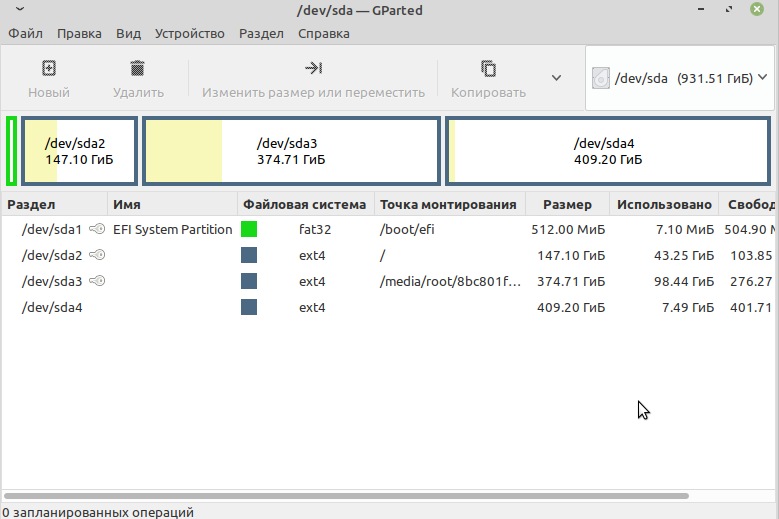

The Filesystem

Learn about the Linux filesystem, the different types of filesystems, partitioning and more.

Boot the System

Learn about the stages of the Linux boot process.

Kernel

The most important part of the Linux system, learn about how it works and how to configure it.

Learn about the different init systems, SysV, Upstart and systemd.

Process Utilization

Learn resource monitoring with top, load averages, iostat and more!

Logging

Learn about system logs and the /var/log directory.

Networking Nomad

Network Sharing

Learn about network sharing with rsync, scp, nfs and more.

Network Basics

Learn about networking basics and the TCP/IP model.

Subnetting

Learn about subnets and how to do subnet arithmetic!

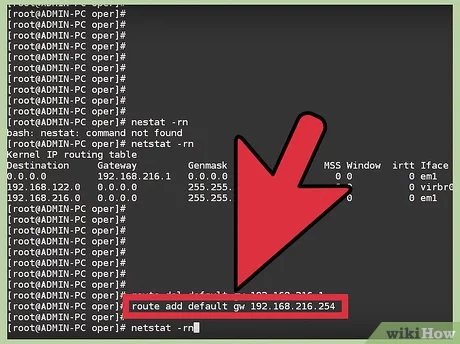

Routing

Learn how packets are routed across networks!

Network Config

Learn about network configuration using Linux tools!

Troubleshooting

Learn about common networking tools to help you diagnose and troubleshoot issues!

Everything and more that you wanted to know about DNS.

Recommended Resources

One of my most highly recommended books!

Extremely comprehensive book for every SysAdmin.

Great comprehensive guide to shell scripting.

For serious Linux-users, great start into kernel programming.

Subscribe

Get updates about new courses and lessons! Subscribe

About Us

The knowledge gained here today was powered by the open-source community.

Contact Us

See a bug? Any complaints? Just want to send a note? Let us know

Источник

How to Create a First C Program on Linux

Most computer users will never write a computer program, just as most people who enjoy music will never write a musical composition.

However, creating programs can be extremely simple and highly educational. It is so simple, in fact, that even people who know almost nothing about computers can begin writing basic programs and experimenting with them almost immediately. It can also be fun, it is often addictive, and it occasionally leads to highly rewarding careers.

The C programming language is an excellent choice for beginning programmers as well as for people who do not intend to become a programmer but just want the experience of creating a program. This is because it is relatively simple, yet powerful and widely used. It is also because C is the basis for many other programming languages, and thus experience gained with C can be applied to those languages as well. In addition, experience with C is useful for obtaining an in-depth understanding of Linux and other Unix-like operating systems, because they are largely written in C.

Linux is a particularly suitable environment for writing programs. This is because, in contrast to some popular proprietary (i.e., commercial) operating systems, it is not necessary to purchase any expensive programming software and, in many cases, the appropriate software is already installed on the computer. Moreover, most major distributions (i.e., versions) of Linux include programming tools on the installation disks (not only for C but also for several other programming languages); such tools can be installed very easily at the time of system installation or separately at a later date.

Three Requirements

Three things are necessary for creating C programs: a text editor, a compiler and a C standard library. A text editor is all that is needed to create the source code for a program in C or in any other language.

Source code (also referred to as source or code) is the version of software as it is originally written (i.e., typed into a computer) by a human in plain text (i.e., human readable characters). Source code can be written in any of the thousands of programming languages that have been developed, some of the most popular of which, in addition to C, are C++, Java, Perl, PHP and Python.

A text editor is a program for writing and editing plain text. It differs from a word processor in that it does not manage document formatting (e.g., typefaces, fonts, margins and italics) or other features commonly used in desktop publishing. C programs can be written using any of the many text editors that are available for Linux, such as vi, gedit, kedit or emacs. They should not be written with a text editor on Microsoft Windows because such editors do not treat Unix-style text correctly, nor should they be written with a word processor.

At least one text editor is built into every Unix-like operating system, and most such systems contain several. To see if a specific text editor exists on the system, all that is necessary is to type its name on the command line (i.e., the all-text user interface) and then press the ENTER key. It it exists, the editor will appear in the existing window if it is a command line editor, such as vi, or it will open in a new window if it is a GUI (graphical user interface) editor such as gedit. For example, to see if vi is on the system (it or some variation of it almost always is), all that is necessary is to type the following command and press the ENTER key:

A compiler is a specialized program that converts source code into machine language (also called object code or machine code) so that it can be understood directly by a CPU (central processing unit). An excellent C compiler is included in the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), one of the most important components of most modern Linux distributions. GNU is an on-going project by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) to create a complete, Unix-compatible, high performance and freely distributable computing environment.

All that is necessary to see if the GCC is already installed and ready to use is to type the following command and press the ENTER key:

An error message such as gcc: no input files indicates that the GCC is installed and ready to use. If there is a message such as command not found, which usually indicates that it has not been installed, the GCC can be installed in the same manner as other software (i.e., from the operating system installation disks or by downloading if from the Internet).

glibc is the GNU project’s implementation of the standard C library. As is the case with the GCC, it is likewise one of the most important components of most modern Linux distributions, which use it as their official standard C library. A library is a collection of subprograms that any programmer can employ to reduce the amount of complex and repetitive source code that has to be written for individual programs. Every Unix-like operating system requires a C library.

The locate command can be used to confirm that glibc is already installed on the system as follows:

If it is on the system, the above command will probably generate many lines on the monitor screen referring to it, particularly referring to the directory /usr/share/doc/.

Information about some of these programs, including the GCC, vi and gedit, can be obtained from the man built-in manual. For example, information about the GCC can be obtained by using the following command:

«Hello, World!» Source Code

The best way to learn about programming is to jump right in and begin writing a very simple program. This approach helps make concepts, that might otherwise seem vague and abstract, make sense, and the positive feedback obtained from getting even an ultra-simple program to work provides a strong incentive to improve it and write the next one.

The traditional first program in C (and almost any other programming language) is very basic and does nothing more than display the phrase Hello, world! on the monitor screen. However, it serves as an excellent introduction to a number of important concepts for absolute beginners. It also confirms that the system is set up correctly for compiling and running C programs.

The first step is to open a text editor and type the source code for this program as follows:

This code should (at least initially) be written exactly as shown. The file should then be saved (i.e., written to the hard disk) using the save command of the text editor.

The file can be given any desired name, but it is usually best to use a name that is descriptive of the program. The name must end with a .c extension in order to indicate to the compiler that it is C source code; if the .c extension is omitted, an error message will be returned. (Extensions usually are not necessary for files in Unix-like operating systems, but this is an exception.) Thus, a good choice for the above example is hello.c.

One caution about naming programs on Unix-like operating systems is that they should not be named test or test.c. This could confuse the operating system, because there is already a built-command named test.

Closer Look at «Hello, World!»

The first line in a C program, which is called a preprocessor directive, always begins with a pound sign ( # ). Preprocessing, which is carried out by the compiler prior to compilation, causes the contents of the indicated header file(s) (which is in glibc) to be copied into the current file, effectively replacing the directive line with the contents of that file. Thus, in this case, the preprocessor directive #include causes the file named stdio.h that resides in glibc to be copied into the source code of hello.c. stdio.h provides the basic input and output facilities for C.

The preprocessor directive is customarily followed by a blank line. As is the case with a number of things in programming, this line is not necessary for a program to function correctly but is, rather, a matter of style. Good style can make programs much easier to read and therefore easier to detect errors and make improvements; it is thus important to develop good style habits right from the beginning when learning programming.

Every C program has exactly one function named main(). A function is a set of one or more statements that are enclosed in curly brackets, perform some operation and return a single value to the program in which they reside; it could also be looked at as a subprogram. The main() function is the starting point of any program; that is, it is where the program begins execution (i.e., running); any other functions are subsequently executed.

A statement is an instruction in a program. Each statement ends with a semicolon. There are two statements in hello.c, both of which are in the main() function.

Parentheses surround the argument list for every function. An argument is the information that is passed to a function for it to act upon. The two functions in this example are main() and printf(); the printf() function is located inside of the main() function. Even if no arguments are actually used, as is the case with main(), the parenthesis are still included.

printf()’s name reflects the fact that C was first developed in the early 1970s when display monitors were rare, and thus all computer output was generally printed out on paper. However, today printf() by default actually sends its output to the monitor screen (referred to as standard output), not to a printer. The f in printf stands for formatted.

Any string (i.e., sequence of printable characters) that is used as an argument to printf() is enclosed in double quotes. The \n at the end of the string in hello.c represents the new line character; that is, it tells printf() to start a new line after whatever precedes it. This causes whatever next appears on the display screen to begin on a new line rather than on the same line as the output of hello.c.

The second statement in the main function is return 0;. It is not necessary for the functioning of this simple program; however, it is included to illustrate how a second statement can fit into a program. It is also included because similar statements are required in more complex programs and thus it is useful to become familiar with it from the beginning.

Each curly bracket is placed on a separate line in this example in order to make it more obvious and to thus make it easier to detect missing or incorrect brackets. However, this is not necessary, and brackets are often included on the same lines as other code, depending on the particular programmer’s style. What is more important is to maintain a consistent style.

C programs are not fussy about the way they are laid out (in contrast to some other programming languages). For example, hello.c could be written very compactly in just two lines without affecting performance as follows:

Such extreme compactness is unusual, however, and it can make more complex programs very difficult to read.

Compiling hello.c

After a program has been planned, written and checked for obvious errors, it is ready to compile. Compilation consists of two main steps, compilation itself (inclusive of preprocessing) followed by linking (i.e., connection of multiple files in a program); the compiler usually performs the linking automatically.

The program hello.c can be compiled with the GCC as follows:

The -o option informs the compiler of the desired name for the executable (i.e., runnable) file that it produces. The name used in this example is hello, but it could just as easily be anything else desired, such as hello.exe, file1 or Bonjour. If the -o option is omitted, the compiler will give the name a.out to the executable file.

Compilation for hello.c should take only about a second or two on a reasonably fast personal computer because the program is so simple. However, compilation can take hours in the case of very large and complex programs.

The ls command (whose purpose is to list the contents of a directory) can be used to confirm both that the source code file was saved and that the new file containing the compiled program was actually created, i.e.,

Possible Problems

Various things can go wrong when writing and compiling software. And they frequently do, particularly for long and complex programs. Fortunately, modern compilers generally provide fairly detailed error messages that facilitate correcting errors in the source code.

There is little that can go wrong with the hello.c program because of its brevity and simplicity, and any errors can prove instructive and are easy to fix. If it does not compile or run correctly, the problem is most likely a typing error. Such errors are among the most frequent sources of problems in programming. Particularly common is forgetting one or more of the curly brackets. This is especially easy to do in programs that contain multiple pairs of brackets, some of which are enclosed in others.

Another common error is the omission of one or more semicolons at the ends of statements. Yet another typical source of problems is forgetting the .c extension at the end of the name of the source code file(s).

Running hello

Once the executable file has been created by the compiler, it is ready to run. This can be accomplished on some systems by merely typing the file name and pressing the ENTER key. On other systems, it might be necessary to precede the file name with a dot and a forward slash and then press the ENTER key, i.e.,

The result will be to write the text Hello, world! on the monitor screen.

It can be instructive to try modifying this program in various ways. They include changing the text message, adding text within printf() that will appear on several different lines on the screen rather than on a single line, adding multiple printf() functions, and eliminating the the preprocessor directive and/or the return 0; line.

hello.c may seem extremely simple and useless, and in some ways it is. However, a little practice with it provides an excellent foundation for writing longer programs that actually do something useful. And they are not much more difficult than hello.c. A slightly more interesting example, and one that introduces some additional C programming concepts, is provided on the page How to Create a Second C Program on Linux.

Created March 21, 2005. Updated March 14, 2006.

Copyright © 2005 — 2006 The Linux Information Project. All Rights Reserved.

Источник