- unixforum.org

- Как работает firmware? (обращение к устройству через usb)

- Как работает firmware?

- Ubuntu Wiki

- Firmware

- What is Firmware?

- Where Do You Get Firmware?

- How is Firmware Used?

- Debugging Firmware Loading

- Initial Step

- Kernel Event Sent to Udev

- Udev Sends Firmware to Kernel

- Kernel Reads the Firmware

- Kernel Gives Firmware to Driver

- Linux firmware

- Contents

- Installation

- Kernel

- Только самое нужное. Избавляем Linux от багажа прошивок для оборудования

- Содержание статьи

- Основы

- Ищем исходники модулей

- Находим все включенные в конфиге модули

- Продолжение доступно только участникам

- Вариант 1. Присоединись к сообществу «Xakep.ru», чтобы читать все материалы на сайте

unixforum.org

Форум для пользователей UNIX-подобных систем

- Темы без ответов

- Активные темы

- Поиск

- Статус форума

Как работает firmware? (обращение к устройству через usb)

Как работает firmware?

Не пойму как именно ОС через firmware обращается к устройству (в моем случае wireless адаптер, через USB).

Читаю о firmware: это прошивка, которую устанавливают в само устройство. Но неужели при установки firmware каждый раз мой GNU/Linux или OpenBSD перезаписывают (перепрошивают) устройство? Т.е. после установки пакета с firmware (набор бинарников) и использовании этого устройства, мы имеем «другое устройство», т.е. перепрошитое?

Я явно чего-то не допопнимаю и хотел бы разобраться с этим вопросом.

С модулями ядра все понятно — функционал подключается к ядру (в случае модулей), я вижу этот модуль через lsmod (в GNU/Linux), а он, в свою очередь, знает как работать с устройством. Есть модуль — есть интерфейс, нет модуля — мы не знаем об устройсве и о том, как с ним работать. А как работает firmware, и как ядро узнает о его наличии, а точнее — о необходимости его использования для общения с устройством? Я сейчас в OpenBSD, было бы здорово, если бы кто-то хотя бы навел на мысль и показал на примере как ПО взаимодействует с устройством именно через firmware в этой ОС.

«Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place.

Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.” (Brian Kernighan)

Источник

Ubuntu Wiki

Firmware

What is Firmware?

Many devices have two essential software pieces that make them function in your operating system. The first is a working driver, which is the software that lets your system talk to the hardware. The second is firmware, which is usually a small piece of code that is uploaded directly to the device for it to function correctly. You can think of the firmware as a way of programming the hardware inside the device. In fact, in almost all cases firmware is treated like hardware in that it’s a black box; there’s no accompanying source code that is freely distributed with it.

Where Do You Get Firmware?

The firmware is usually maintained by the company that develops the hardware device. In Windows land, firmware is usually a part of the driver you install. It’s often not seen by the user. In Linux, firmware may be distributed from a number of sources. Some firmware comes from the Linux kernel sources. Others that have redistribution licenses come from upstream. Some firmware unfortunately do not have licenses allowing free redistribution.

In Ubuntu, firmware comes from one of the following sources:

- The linux-image package (which contains the Linux kernel and licensed firmware)

- The linux-firmware package (which contains other licensed firmware)

- The linux-firmware-nonfree package in multiverse (which contains firmware that are missing redistribution licenses)

- A separate driver package

- Elsewhere (driver CD, email attachment, website)

Note that the linux-firmware-nonfree package is not installed by default.

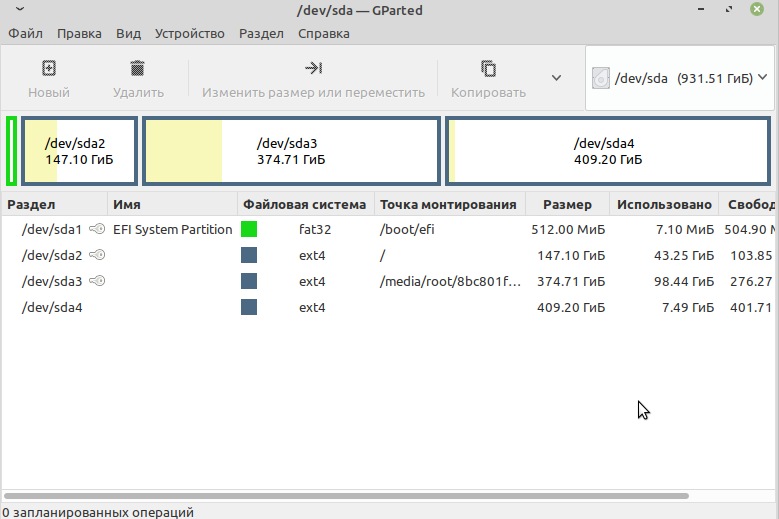

The firmware files are placed into /lib/firmware. If you look inside there on your Ubuntu installation you will see hundreds of firmware files that have been installed by these packages.

How is Firmware Used?

Each driver for devices that require firmware have some special logic to retrieve firmware from files in /lib/firmware. The basic process is:

- Driver requests firmware file «ar9170.fw»

- The kernel sends an event to udev asking for the firmware

- The udev program runs a script that shoves the data in the firmware file into a special file created by the kernel

- The kernel reads the firmware data from the special file it created and hands the data to the driver

- The driver then does what it needs to do to load the firmware into the device

If everything goes well you should see something like the following in your /var/log/syslog:

If there’s an issue, you may see something like the following:

Debugging Firmware Loading

Luckily, the firmware loading process is not too difficult to watch in action. Using the following debugging steps we can pin point what step in the process is failing.

Initial Step

First, ensure that the firmware file is present. If you are missing the firmware file, try searching on the web for a copy of it. If you find it, consider filing a bug against linux-firmware if the firmware has a redistribution license or against linux-firmware-nonfree otherwise.

If the file is present, check that it’s not empty using ‘ls -l’:

The size of the file is the number listed after the user and group owners («root» and «root» in this case). It should be non-zero. At this point, you may want to search the web for an md5sum hash of the file and compare it to this file, but it’s not likely that the file is corrupted. If the firmware is corrupted, you will likely see an error message from the driver stating that the firmware was invalid or failed to upload anyways.

At this point we’ve verified that the firmware file exists, but wasn’t uploaded. We need to figure out which of steps 2-4 mentioned above are failing. Let’s start with step 2.

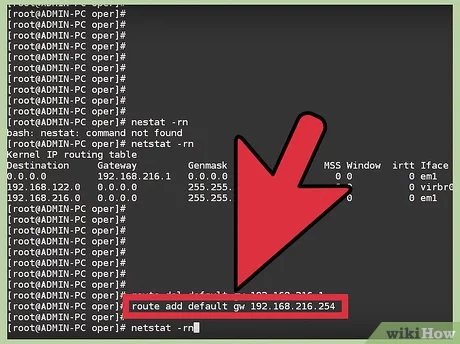

Kernel Event Sent to Udev

The second step involves the kernel sending an event to the udev subsystem. Luckily, there’s a handy tool we can use for monitoring these event messages: udevadm. Start with your driver unloaded. Then execute:

Now load your driver. Sometimes loading the driver alone will cause a firmware request. Other times, as with the e100 driver, you will need to do something to initiate a firmware request. In the case of the e100 driver, the firmware is requested after the user tries to bring up the ethernet interface by running ‘ip link set eth0 up’.

Once you have initiated a firmware request you should see a udev event that looks like the following:

There are three key pieces of information in this event:

- ACTION=add: This means the event is for the addition of the devices, as opposed to the removal of the device

- SUBSYSTEM=firmware: This means the event is a firmware request event

FIRMWARE= : This is the filename of the firmware requested by the driver.

If you do not see an event with these three items, then the kernel request is not being propagated to udev. You should file a bug at this point against the udev package. If you do see this event, continue to the next step.

Udev Sends Firmware to Kernel

Now that udev has seen the firmware request, it has to decide how to process it. There should be a «rules» file in /lib/udev/rules.d/50-firmware.rules with a single udev rule:

9.10 (Karmic Koala) and earlier:

10.04 (Lucid Lynx) and later:

This rule tells udev to run the firmware program, which may be found in /lib/udev/, whenever it sees an event with both ACTION=add and SUBSYSTEM=firmware. In 9.10 and earlier, the firmware program will be passed the rest of the udev event information as environment variables. In 10.04 and later, the firmware filename and device path will be passed as parameters.

We can watch udev process the event by turning on extra logging:

When you initiate a firmware request, udev will log what it does with the event to /var/log/syslog. For example, you should see something like:

If you do not see firmware.sh get run, then you likely have an issue with your udev rules. Check for any custome udev rules you have in /etc/udev/rules.d. Any files in this directory will override files with the same name under /lib/udev/rules.d. Rules in /etc/udev/rules.d may also prevent the firmware rule from executing properly. If you have any issues at this step you should seek help from the community. If you believe you have found an issue in udev, feel free to open a bug.

After you have debugged udev execution, you should return the logging output to the normal level:

Kernel Reads the Firmware

If the firmware.sh script has been executed by udev, any errors it encounters should show up in your /var/log/syslog file. If you see any errors here they may be caused by the firmware.sh script (which is part of udev), or by the kernel. If you see the following error:

you should open a kernel bug. If you see any other error, you should open a bug against udev.

Kernel Gives Firmware to Driver

If the firmware loading process properly runs firmware.sh without an error, but the driver complains about the firmware, one of two things may be wrong. First, the firmware file may be incorrect or corrupted. You can try to reinstall the firmware or get the firmware from another source. Second, there may be an issue with the driver itself. If you have tried all the firmware versions you could find, you should open a kernel bug.

Kernel/Firmware (последним исправлял пользователь khadgaray 2013-12-11 08:01:04)

Источник

Linux firmware

Linux firmware is a package distributed alongside the Linux kernel that contains firmware binary blobs necessary for partial or full functionality of certain hardware devices. These binary blobs are usually proprietary because some hardware manufacturers do not release source code necessary to build the firmware itself.

Modern graphics cards from AMD and NVIDIA almost certainly require binary blobs to be loaded for the hardware to operate correctly.

Starting at Broxton (a Skylake-based micro-architecture) Intel CPUs require binary blobs for additional low-power idle states (DMC), graphics workload scheduling on the various graphics parallel engines (GuC), and offloading some media functions from the CPU to GPU (HuC). [1]

Additionally, modern Intel Wi-Fi chipsets almost always require blobs. [2]

Contents

Installation

For security reasons, hotloading firmware into a running kernel has been shunned upon. Modern init systems such as systemd have strongly discouraged loading firmware from userspace.

Kernel

A few kernel options are important to consider when building in firmware support for certain devices in the Linux kernel:

For kernels before 4.18:

CONFIG_FIRMWARE_IN_KERNEL (DEPRECATED) Note this option has been removed as of versions v4.16 and above. [3] Enabling this option was previously necessary to build each required firmware blob specified by EXTRA_FIRMWARE into the kernel directly, where the request_firmware() function will find them without having to make a call out to userspace. On older kernels, it is necessary to enable it.

For kernels beginning with 4.18:

Firmware loading facility ( CONFIG_FW_LOADER ) This option is provided for the case where none of the in-tree modules require userspace firmware loading support, but a module built out-of-tree does. Build named firmware blobs into the kernel binary ( CONFIG_EXTRA_FIRMWARE ) This option is a string and takes the (space-separated) names of firmware files to be built into the kernel. These files will then be accessible to the kernel at runtime.

Источник

Только самое нужное. Избавляем Linux от багажа прошивок для оборудования

Содержание статьи

С железом нередко бывает так, что одного драйвера в пространстве ядра ОС для его работы недостаточно. Нужна также прошивка (firmware), которая загружается в само устройство. Точный формат и назначения прошивки зачастую известны только производителю: иногда это программа для микроконтроллера или FPGA, а иногда просто набор данных. Пользователю это не важно, главное, что устройство не работает, если ОС не загрузит в него прошивку.

В свободных операционных системах прошивки нередко вызывают споры. Многие из них распространяются под несвободными лицензиями и без исходного кода. Авторы OpenBSD и ряда дистрибутивов GNU/Linux считают это проблемой и со свободой, и с безопасностью и принципиально не включают такие прошивки в установочный образ.

Если у тебя есть устройство, которое требует прошивки, и тебе нужно, чтобы оно работало, вопрос лицензии прошивки становится чисто академическим — от необходимости иметь ее в системе и загружать ты никуда не уйдешь.

Полный набор из linux-firmware занимает более 500 Мбайт в распакованном виде. При этом каждой отдельно взятой системе требуется только небольшая часть этих файлов, остальное — мертвый груз.

Даже в современном мире с дисками на несколько терабайт еще много случаев, когда размер имеет значение: встраиваемые системы, образы для загрузки через PXE и подобное. Хорошо, если о board support package позаботился кто-то другой, но это не всегда так.

Если ты точно знаешь полный список нужного железа, можно извлечь файлы вручную. Впрочем, даже в этом случае найти нужные файлы может быть непросто — linux-firmware представляет собой не очень структурированную кучу файлов, и списка соответствия файлов именам модулей ядра там нет. А если ты хочешь дать пользователям возможность легко собрать свой образ, тут и вовсе нет выбора — нужно автоматическое решение.

В этой статье я расскажу о своем способе автоматической сборки. Он неидеален, но автоматизирует большую часть работы, что уже неплохо. Писать скрипт будем на Python 3.

Примеры кода в статье упрощенные. Готовый и работающий скрипт ты можешь найти на GitHub.

К примеру, можно им просмотреть список прошивок для включенных в .config драйверов сетевых карт Realtek.

Основы

В ядре Linux нет глобального списка прошивок и кода для их загрузки. Каждый модуль загружает свои прошивки с помощью функций из семейства request_firmware . Логично, если учесть, что процедура загрузки прошивки у каждого устройства разная. Соответственно, информация о нужных прошивках разбросана по множеству отдельных файлов с исходным кодом.

На первый взгляд, некоторую надежду дает опция сборки FIRMWARE_IN_KERNEL . Увы, на деле она встраивает в файл с ядром только файлы, которые ты явно укажешь в EXTRA_FIRMWARE . Так что файлы все равно сначала придется найти.

Поиск по вызовам request_firmware() тоже не очень перспективен. Некоторые модули поддерживают несколько разных прошивок, да и имя файла часто хранится в переменной. В качестве примера можно посмотреть на фрагмент кода из драйвера сетевой карты Intel e100.

К счастью для нас, модули должны указывать нужные им файлы прошивок с помощью макроса MODULE_FIRMWARE() . Пример можно найти в e100. Этот макрос определен в файле include/linux/module.h .

Именно из вывода этого макроса берется информация о прошивках, которую можно увидеть в выводе утилиты modinfo .

В ряде случаев можно было бы обойтись одной modinfo . Если у тебя есть собранное ядро и возможность его загрузить, ты можешь просмотреть вывод modinfo для каждого нужного модуля. Это не всегда удобно или вообще возможно, так что мы продолжим искать решение, для которого понадобится только исходный код ядра.

Здесь и далее будем считать, что все ненужные модули отключены в конфиге сборки ядра (Kconfig). Если мы собираем образ для конкретной системы или ограниченного набора систем, это вполне логичное предположение.

Ищем исходники модулей

Чтобы собрать список имен файлов прошивок, мы сначала составим список всех файлов исходного кода ядра, где они используются. Затем мы прогоним эти файлы через препроцессор из GCC, чтобы раскрыть все макросы, и извлечем собственно имена нужных файлов.

Находим все включенные в конфиге модули

Это самая простая часть. Конфиг сборки ядра имеет простой формат «ключ — значение» вроде CONFIG_IWLWIFI=m . Значение может быть n (не собирать), y (встроить в ядро) или m (собрать в виде модуля).

Нас интересуют только ключи, а какое значение там, y или m , нам не важно. Поэтому мы можем выгрести нужные строки регулярным выражением (.*)=(?:y|m) . В модуле re из Python синтаксис (. ) используется для незахватывающих групп (non-capturing group), так что захвачена будет только часть в скобках из (.*)= .

Продолжение доступно только участникам

Вариант 1. Присоединись к сообществу «Xakep.ru», чтобы читать все материалы на сайте

Членство в сообществе в течение указанного срока откроет тебе доступ ко ВСЕМ материалам «Хакера», позволит скачивать выпуски в PDF, отключит рекламу на сайте и увеличит личную накопительную скидку! Подробнее

Источник